This articles belong to PHOTOCENTRALASIA.COM (ANAHITA GALLERY) and are a great source for us, Western-centrics, to learn about Photography in Central Asia.

- 19th and Early 20th Century Photography

- The Soviet Period

- Modern Uzbek Photography

19th and Early 20th Century Photography

Our oldest photographic material from Central Asia dates back more than one hundred years. After several centuries of political instability, the early 19th C. saw the establishment of three independent kingdoms, the Khanates of Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand. Slave-based agriculture expanded, trade increased, and new demands for luxury goods brought about an artistic revival in Central Asia. At about the same time, increasing British activity in Afghanistan propelled commercial and military interests in Tsarist Russia to look towards Central Asia. These interests hoped to find not only a bulwark against British influence along their southern borders, but also a colonial marketplace in which Russian goods could viably compete, and a rich source of raw materials, particularly cotton.

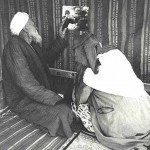

Soon after 1850, a series of hard-fought battles brought Russian troops across the Kazakh plains, and between 1865 and 1884, Russian forces took complete political control of the oases towns, with the Emir of Bukhara alone retaining a nominal local sovereignty. The arrival of photographers in Central Asia roughly paralleled the arrival of Russian troops and Russian administrators. The centers of photographic activity were the Russian held towns of Khokand and Samarkand, and the administrative city of Tashkent. Prior to the Russian conquest, only a few earlier travelers had come to the oasis towns. Even if they had the ability and the desire to do so, taking photographs would have excited the suspicions and the animus of the local rulers. So for our purposes, and in so far as we have found the sources, the possibility of photography in Central Asia begins only around 1860, and the reality, more likely, about 1870.

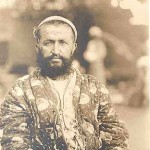

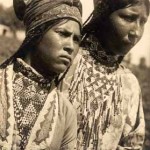

Up until the end of the 19th century, it was very likely that photographers were outsiders, foreign to Central Asia and its indigenous culture. Even in the late 19th century, only the most cosmopolitan elements of urban society would have considered commissioning a portrait. For several hundred years prior to this time, portraiture in any form was not a traditional art in Central Asia. Thus, is analyzing these photographs, we should consider the foreign photographer’s point of view.

Despite the inherent exoticism of the subject matter, Central Asian photographs have a more immediate and documentary quality than much Near Eastern or East Asian photography of the period. Central Asian photography has never been primarily market driven. While there was some production of souvenir photographs for sale, largely in postcard form, many photographers appear to have been gifted amateurs. Others worked at the behest of governmental institutions, notably Alexander Kuhn, the compiler of the albums of more than 1200 photographs commissioned by Governor General von Kaufmann in 1870, and Samuel Martinovich Dudin, who assembled vast photographic and ethnographic collections between 1893 and 1914. The intent of these institutional collections, whether military or scientific, was to provide the new rulers with an encyclopedic catalog of the regional architecture, industry and customs of the local population.

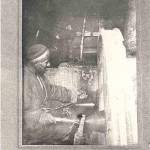

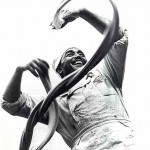

In urban Central Asia the sources are comparatively rich. There are many photographs of the stunning architectural monuments of the Timurid and Shaibanid period. The genre scenes most typical of urban photography are of handicraft production, the open marketplace and various public entertainments. Individual and family portraits are not as common, but there is great dignity, maintained even under duress, in many of these photographs. There is less arrogance in the photographer’s approach, and the sitters’ attitude is not as submissive as one finds in other colonized parts of the world.

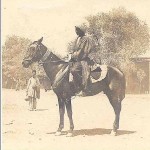

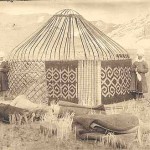

Photographs taken outside the cities are often less intimate. There are relatively large numbers of photographs of Kirgiz nomads, and relatively few photographs of Turkoman nomads taken in steppe locales until the end of the century. Turkomans were engaged in sporadic military resistance to Russian occupation. It was not a situation that encouraged photographic expeditions into the steppe.

The Soviet Period

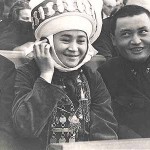

The October Revolution of 1917 radically affected the visual arts in every part of former Tsarist Russia. By the mid-twenties, the style, content and message of photography had completely changed. In Central Asia, pre-Soviet photography had been about Central Asian people and culture, whether the photographer’s intent was romantic or scientifically documentary. The subject of the new Soviet photography was the dynamics of change. Photojournalism or “action photography” was widely recognized by Soviet leaders as a powerful tool to convey new political ideas. Photographs depicteda moribund Central Asia coming to life through contact with progressive Soviet forces. Soviet society might be represented as a live Russian, a Russian newspaper, a tractor or a smokestack, but the Russian element was always dominant and the Central Asian subordinate. The Russians were teachers and the Central Asians willing pupils.

The best-known early Soviet photographers working in Central Asia were Russians. The artist Max Penson fled his hometown of Velizh in Belorussia during the pogroms of 1915, and settled in Kokand, where he taught drawing. By 1925 he had become a professional photographer working at the newspaper Pravda Vostoka. Penson was friendly with Rodchenko, Zelma and Sergei Eisenstein, and his work reflected the same modernist concerns. Eisenstein wrote in 1940:

“There cannot be many masters left who choose a specific terrain for their work, dedicate themselves to it completely and make it an integrated part of their personal destiny… It is, for instance, virtually impossible to speak about the city of Fergana without mentioning the omnipresent Penson who traveled all over Uzbekistan with his camera. His unparalleled photo archives contain material that enables us to trace a period in the republic’s history, year by year and page by page. His whole artistic development, his whole destiny, was tied up with this wonderful republic.” From Erika Billeter, Usbekistan, Documentary photography 1925-1945 by Max Penson, Benteli Verlags AG, Wabern-Bern, 1996.

At the start of World War II, Penson’s career was affected by growing anti-Jewish sentiments and he was given less important newspaper work. His dismissal in 1948 effectually ended his career as an artist, and he died in 1959, a deeply disappointed, broken man.

Georgi Zelma was born in Tashkent in 1906. In 1921, when he was fifteen, he and his mother left Central Asia for Moscow, making the five-week journey in a freight car. He joined the photography club in his primary school, and found work first for the Proletkino studio, and then for Russfoto, the agency supplying photographs to the foreign press. He returned to Central Asia as correspondent for Russfoto in 1924. Georgi Zelma’s work in Central Asia is often focused on the decisive moments of emancipation and achievement or the crucial instant of contact between the old world and the new. His artistic concerns are thoroughly modernist, and his sense of composition is both dramatic and seemingly effortless. Zelma’s photography for Izvestia in the 1930’s brought him attention for his work on construction during the first Five Year Plan, but he is best known in the West for his exceptional work as a war photographer during World War II. In later years he worked for the magazine Ogonyok and the Novosti Press Agency. He died in 1984.

Modern Uzbek Photography

Since the breakup of the former Soviet Union, photographic artists from the newly independent Republic of Uzbekistan have produced challenging work that turns the Soviet propaganda function of photography on its head. During the communists period photography was at the service of the state, and its primary theme was the “progress” brought about by interaction with European/Socialist culture. This transfer of culture and ideas was entirely one way, and very few of the photographers of the period were Central Asian themselves.

Over the last fifteen years a few brave photo-journalists have begun taking photographs that are both socially critical and artistically demanding. In part, their work may be seen as a reaction to the clichéd sentimentality of the photos of the past seventy years: there are no more pictures of smiling peasants or overly-restored-mosques-turned-museums. One of the most refreshing aspects of the new photographic works is that they are meaningful as purely personal artistic creations – rather than expressions of ideology as in the past.

Marat Baltabaev and Anatoly Rahimbaev contrast their work to what they call ‘postcard photography’. They say their work is “photographing life”, by which they mean real life. The peeling paint, dirt roads and generally disheveled air of their pictures is at least as representative of modern Central Asian life as the ancient monuments and government sponsored “folklore” of the Communist period. Life in Central Asia has never been easy; earthquakes and famine, invasions and tyrannical rulers have been all too common. Connections with the outside world ebbed and flowed along with political fortune.

Today the people of Uzbekistan are emerging from 140 years of Russian rule – there is a palpable sense of taking stock of the present. If they find themselves in strange clothes, speaking a foreign language, surrounded by oppressive buildings and monuments, with land and water polluted, well, they’ve seen worse. The people in the modern Uzbek images are survivors from a long line of survivors. The past may have been dark but the future is really …interesting.

Baltabaev (b. 1961) and Rahimbaev (b. 1957) are freelance photographers who have developed professional careers in advertising and journalism. Neither studied photography in school. Baltabaev earned a technical degree in electro-mechanics before taking up photography in 1983. Rahimbaev initially studied geology, began his photographic work in 1985, and now works at B.V.V. (Business Vestnik Vostoka), a Tashkent newspaper. Dina Khojaeva, also from Tashkent, is a commercial photographer working extensively within the media and entertainment community, and is the daughter of early Soviet photographer Max Penson.

Postcards

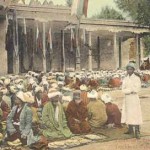

The first postcards with Central Asian images date to just before the turn of the century. These otkrit, “open” letters were quickly adopted both for local use and for sale to the tourists that first arrived in substantial numbers around the same time. Many postcards were printed by firms located outside of Central Asia. Before the 1917 Revolution, Nabholz and Co. in Moscow, and Granbergs Brekfort in Stockholm appear to have been the largest outside firms. Central Asian firms located in Andijan, Ashkabad and Kokand are also credited on early postcards.

Many essentially documentary photographs made by an earlier generation of photographers were reproduced as postcards with generalized titles characteristic of the genre. Sometimes these bear incongruous or implausible messages – greetings in colloquial Russian from steppe nomads and less than friendly native girls. Photographs made specifically for postcard production range from uninspiring views of government buildings to the more dramatic “native” themes. Many of the cards that remain are titillating or deliberately exotic; crippled beggars, lepers and dervishes, faked executions and contrived harem scenes. Until the Soviet period, postcards rarely departed from the familiar, colonial themes of native types, landmarks, local handicraft production, markets and public entertainments.

By the mid-twenties postcards had taken on the same propagandistic functions as documentary print photography, and carried the same underlying message of revolutionary fervor and social change. Postcard design was closely related to public posters, in which collage reduced the individual to one of the crowd, and political slogans were superimposed on otherwise banal images. Native types and other exotic themes remained popular throughout the twenties and thirties, but photographs of new government buildings and newer monumental statues – first of Lenin, then of Stalin – are found ever more frequently.

via Anahita Gallery:

Anahita Gallery, Inc specializes in vintage and modern international photography with a focus on Russia and Central Asia. We show vintage work by Bulla, Dudin, Eremin, Grinberg, Penson, Rodchenko, Shagin, Shokin, Zelma and others. Our contemporary Russian photographers include Boris Savelev, Sergei Gitman, Elena Darikovich, Alexander Lapin, Igor Mukhin, Alexander Slyusarev, Boris Smelov and Maria Snigerevskaya. Other contemporary artists include Uzbekistan photographers Marat Baltibaev and Anatoly Rahimbaev, Irish photographer Trina McKillen and Columbian photographer Hector Acebes.