Matthew Monteith: Czech Eden

by Michael Famighetti

After the Velvet Revolution marked the end of Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime tourists from across Western Europe, and the world, arrived by the busload in Prague to marvel at this spire-marked capital that had effectively been off limits, for a half century, to those outside the Soviet empire’s reach. Naturally, many of these visitors took photographs, proof that they had visited this fairytale-like place where time had seemingly stood still. Digital photography was not yet the norm, so a friend of mine, who worked in a photo lab near the center of Prague processed, day after day, photographs of the Charles Bridge, the Castle, and the famed astronomical clock, bemoaning that for all their good intentions, the photographs hit the same flat notes again and again. They were fine images to show to their friends back home but they ultimately revealed very little, beyond what Susan Sontag called “the indisputable evidence that the trip was made.”

Amateur photographs, however, can be resonant, revealing, and accomplished in their own right. Though Matthew Monteith is a prodigiously skilled, highly technical photographer, he understands this well. During his first visits to the Czech Republic in the 1990s, he developed an appreciation for Czech vernacular photography and postcards from the 1920s and ‘30s. In them he found scenes of day-to-day life that were that were at times sentimental, romantic, humorous, and mysterious, but almost always anonymous. Although these authorless photographs had functioned primarily as aide-memoire for someone unknown to Monteith, he was equally stuck by both their senses of idealism and uncanny. He then set out to create a body of work inspired by the fragmented stories to which these images had alluded.

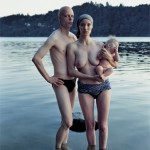

“Czech Eden” is named after an officially protected park in the Czech Republic, a place known for its vertiginous sandstone formations and remarkable natural beauty. However, few of Monteith’s photographs depict this preserve. Instead, most were taken in or around Prague, in his friends’ homes, on the streets, or in small towns where it is as likely to find a centuries-old castle as an ominous nuclear cooling tower looming large. Although it is important to know where these photographs were taken, ultimately their meanings are not contingent upon place. “Czech Eden” should not be viewed as a documentary project. It is not a literal description of life in the Czech Republic but instead an open-ended allegory, one that references old images but articulates a vision of contemporary life that is at times disquieting and humorous. In one image a boy plays amidst the ruins of a brightly colored building; in another a man sitting in a vertigo-inducing patterned chair contemplates a hammer at his side. Elsewhere, an elderly couple, their clothing tattered, take a break from cutting wood, to pose for a picture.

They seem happy, or at least willing to oblige the photographer, but standing far apart the viewer can be forgiven for assuming that they don’t seem entirely happy with one another. Whether a landscape or a portrait, each image, however visually seductive it may be, is underscored by a revealing, albeit often disquieting, tension. The great Czech writer Ivan Klima identifies this quality in his essay in Matthew Monteith’s forthcoming monograph, suggesting that these photographs are “like a tour of the world as perceived” by Kafka, a Czech writer (though he wrote in German) known for his portrayals of alienation in the modern world. Monteith’s “Czech Eden” does not picture anything resembling paradise but instead a place that conjures a feeling of loneliness that is a basic, if unsettling, part of experience today—a mood of alienation that would be as familiar to my friend processing those pictures as to the people who took them in earnest.

via www.matthewmonteith.com

book available at Photoeye

thank you very much